GUT REACTIONS: Ashes & Embers (1982) asks "Who gets to be American?"

Similar to "Cowboy Carter" by Beyoncé, "Ashes and Embers," dir. Haile Gerima, explores critical questions about how Black identity fits into American-ness.

In my GUT REACTIONS series, I contextualize films with their cultural significance.

It’s two days after Memorial Day and I’m standing in a Shake Shack line that presses down on me with significance.

The last time I shouldered this cheap nylon carry-on from Ross — a barely chic substitute for the Baggu luggage I had waited too long to buy — was when I took the Amtrak to NYC.

As always, when I travel to the Big Apple, my goal is to see movies. In February, it was Metrograph. In April, the Film @ Lincoln Center programming was top of mind.

I was curious about Ashes and Embers (1982), a film directed by Haile Gerima. Film @ Lincoln Center was closing out April with an ode to the L.A. Rebellion, a collective of Black filmmakers in Los Angeles who were largely active throughout the 70s and 80s.

I had arrived at the Center that Saturday, brimming with excitement. I did what I relish doing: I bought a ticket in person, at the box office. I was way too early for the movie, so I asked the personnel if I could just stick my head into the free talk that was wrapping up for L.A. Rebellion: Then and Now.

I watched Gerima’s son, Merawi; Denise Fernandes, another fellow filmmaker; and programmer Clare Diao, who put together the films, chitchat about Black culture in the U.S., and thread the needle with their experiences as different kinds of members of the Black diaspora (African, Carribbean, American, European).

And after a Q&A — and after the Q&A still, where I picked one of the directors’ brains about Ryan Coogler’s Sinners and the work of Jordan Peele — I headed across the street to watch Ashes and Embers.

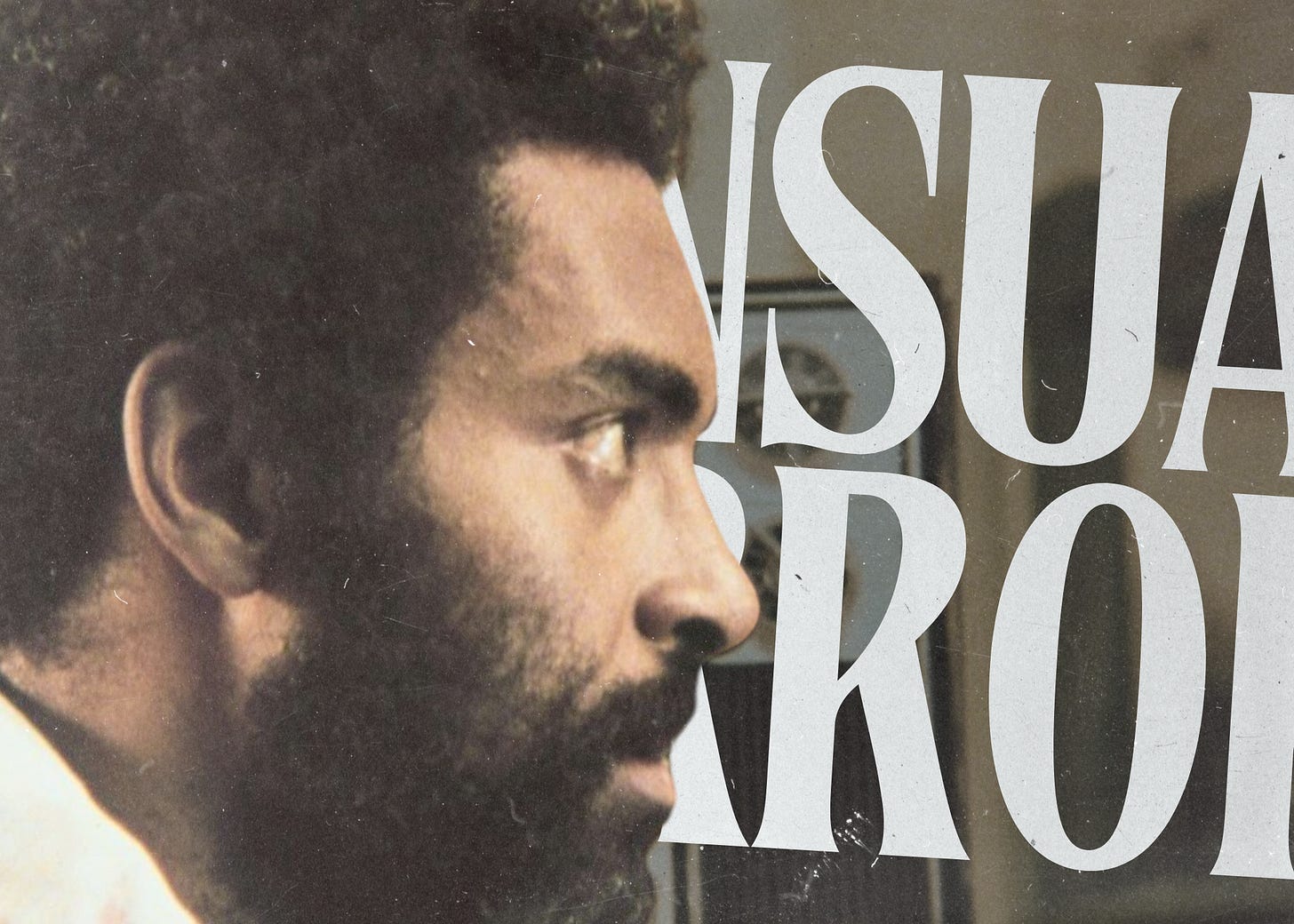

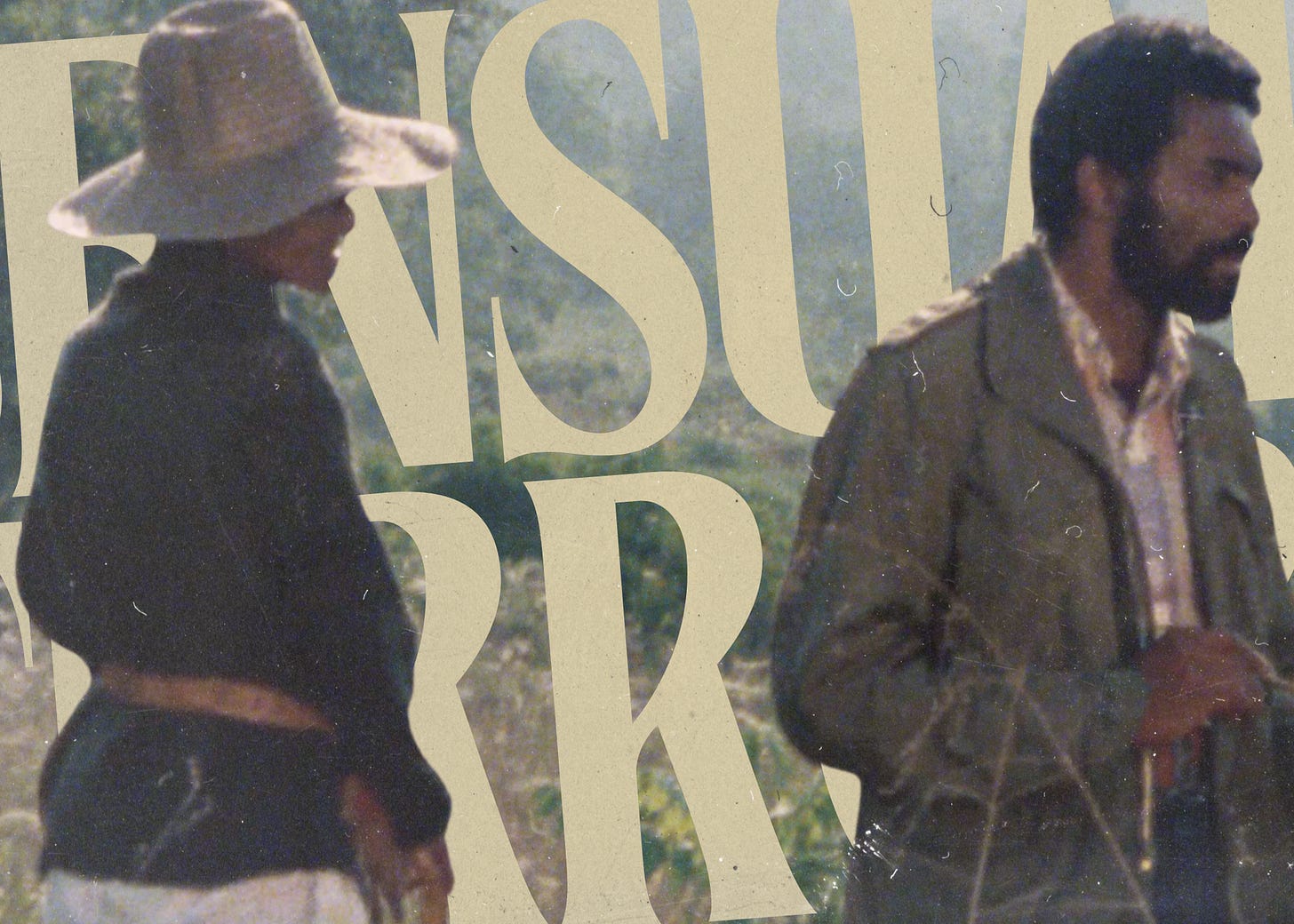

The film paints a moving portrait of Nay Charles, an African-American man who has returned home from the Vietnam War, indelibly marked. The film is split between the D.C. studio apartment where Nay Charles and his partner deal with his PTSD and his subsequent nightmares; his idyllic grandmother’s house down South; and Los Angeles, the site of a war buddy’s apartment.

A large chunk of the movie takes place at home in D.C. Tensions brew due to Nay Charles’ anger issues, listlessness, inability to hold down a job and inability to just get over the horrors he witnessed (and meted out) in the war.

The conflict isn’t one overseas, fought some eight years prior with guns. The real conflict the storm in Nay Charles’ mind. The real conflict exists between the ideologies of Nay Charles’ “thought daughter” wife and her highfalutin friends — men and women like the ones I’ve known, who pursue African American studies and sociology degrees from Howard University — the lived experience of Black people.

The real conflict lies in what Haile Gerima underscored in a Q&A session after the film: What does it mean to be Black and fight for your country, when Black people aren’t considered a real “part” of that country?

Looka there, looka in my hand

The grandbaby of a moonshine man

Gadsden, Alabama

Got folk down in Galveston, rooted in Louisiana

Used to say I spoke too country

And the rejection came, said I wasn't country 'nough— “Ameriican Requiem,” Beyoncé

Similar to Nay Charles’ wife, I took a lot of women’s and gender studies classes in undergrad. Like many of my core friends from this time, I damn near could have minored in WGS. One of the courses I took on transnational feminism explored the gendered violence of the U.S. military-industrial complex.

I remembered the discomfort and brilliance I uncovered with one of my essays, where I spoke to my own family’s intertwined history. I made note of how my mom followed my dad all over Creation, from base to base, supporting his decision to enter the military.

Like Nay Charles and his wife, my dad and I would butt heads over the morality of joining the U.S. military.

As time has gone on, I have more compassion for my dad — and can say that maybe his joining the army wasn’t such a bad thing. The more evil thing was how the U.S. government preyed and continues to prey upon young men of little means.

The U.S. government dangles the promise of pre-paid education, good salaries, stable work, lifetime benefits, and societal legitimization for the small sacrifice of one’s physical well-being and sanity.

I can’t fault my dad for making the choices he did — the high-level philosophical question of it all be damned— to survive in this anti-Black, profits-over-people, White-supremacist framework.

I cried a lot during Ashes and Embers, but I cried the most during scenes of Nay Charles at his grandmother’s house. Away from the harsh realities of “real life,” such as the lack of real care provided to veterans or resources for re-integration into civil life, Nay Charles could be nurtured and doted upon.

I couldn’t help but think of my father, a child of the 60s, who spent 21 years in the military. I couldn’t help but think of my now late grandmother, her easy Southern drawl, her glittering eyes, and her goodwill expressed in stewed collard greens with chunks of ham.

Although it was edited for slight comedic value, the montage of Nay Charles’ grandmother heaping large helpings of classic Southern fare put a lump in my throat. How many times had my grandmother done the same for my father?

And how many times, no matter how sophisticated his urban life became, had my dad returned to South Carolina to ground himself? To remember his roots?

And the rejection came, said I wasn't country 'nough

Said I wouldn't saddle up, but

If that ain't country, tell me what is?

Plant my bare feet on solid ground for years

They don't, don't know how hard I had to fight for this

When I sang my song— “Ameriican Requiem,” Beyoncé

I write this from Union Station in Washington, D.C. Like Nay Charles, my dad had made the drive many a time from D.C. down into the thickets, across the stretches of highway with God-fearing billboards and roadside diners, along the snaking routes to a slower pace of life.

My dad will make the drive again for to celebrate the 4th of July with this family, while I will be at one of Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter tour dates.

To some intellectual Blacks, both of these trips may be an abomination.

America and Independence Day are nothing for the African American to celebrate.

My answer is “Yes, and…”

Since adolescence, I have never been able to shake off the history of slavery. I spent my formative years going to school near one of the most important slave ports in the country. I felt the spirits of blown-apart Confederate soldiers lingering on the island where I attended Mass on Sundays.

And it’s for that reason, Cowboy Carter means the world to me. Black folks, we built this country. Black folks also created country music, much to everyone’s chagrin. (See Tuesday’s debacle at the American Music Awards, involving Nigerian-American artist Shaboozey and his segment cohost Megan Moroney, and what the teleprompter said about the origins of the genre.)

Every year, especially since coming into my Black consciousness in college, I have posted something on Instagram summing up what 4th of July means to me as a Black American: Up until very recently, my ancestors were not free on July 4, 1776, but dammit, I’m going to enjoy my day off and hopefully, some barbecue up to my Black American Southern standards.

This year, especially, I will don stars and other emblems of Americana on July 4. I will dye my1 hair blue, I will get my nails done in blood red and I will set everything off with icy silver.

I will celebrate my foremothers who had to fight to vote, to drink out of clean water fountains, to be seen as legitimate in a country they did not choose.

As I contemplate my options in the Shake Shack line, I glimpse the tell-tale sign of an 8th grade edgelord: a Make American Great Again hat. As the local subreddits have pointed out, it’s a classic purchase for tweens on a field trip.

Washington, D.C. isn’t a mandatory school excursion for me; it’s my real life. Work keeps bringing me to Capitol Hill, so I know MAGA movers and shakers don’t wear the red hats.

It’s often a prop or a photo op. Real politicians wear it for camp. Republicans with real money subscribe to quiet luxury like any other modern capitalist does.

As I move up in line, another red hat in the exact same shade catches my eye. I saw Parkwood’s Instagram Story a few hours earlier, as I staved off delayed-train ennui. I know what this one is about.

After punching my order into my kiosk, I giddily gesture at the felt hat attached to the handle of her rollerbag.

Her water wave wig covers her ears — I don’t know if, like me, she’s been listening to CC to get her through endless Amtrak updates and a lack of gate being called.

She tilts her head, eyebrows raised.

“You’re going to Cowboy Carter, right?”

A soft smile cracks her face. “Yes!”

As the MAGA pre-teens mill about — one with pitiful peach fuzz has been looking at me curiously, furtivegly, this whole time, as if he’s never seen a Black person up close before — me and the other Black lady kiki about Beyoncé. We both went to the Renaissance tour. Somehow, I end up admitting forbidden knowledge: The Las Vegas tickets are $150 a pop right now…

We’re the same kind of nuts, I realize. Her food is ready. “Have fun tomorrow!”

It isn’t an empty platitude coming out of my mouth, but a prayer of petition.

I’ll cry when it’s my turn on the 4th of July — the same way I cried watching Ashes and Embers.

Sure, the acting was phenomenal, and the writing, combined with the camera work, had a realism that bowled me over. Likewise, that Creole lady will sing and dance her ass off, again, and it will be a phenomenal spectacle.

But the real value of Ashes and Embers and Cowboy Carter is not just the finesse, but the message. The question of “Who gets to be American?” cuts deep, especially at a time like this.

Ashes and Embers is distributed by ARRAY, a media platform and collective founded by iconic director and my current favorite Substacker, .

Not my hair, but the real human hair that I bought…