What do David Cronenberg, the sex club and Catholic art have in common?

Body horror and Catholicism go hand in hand.

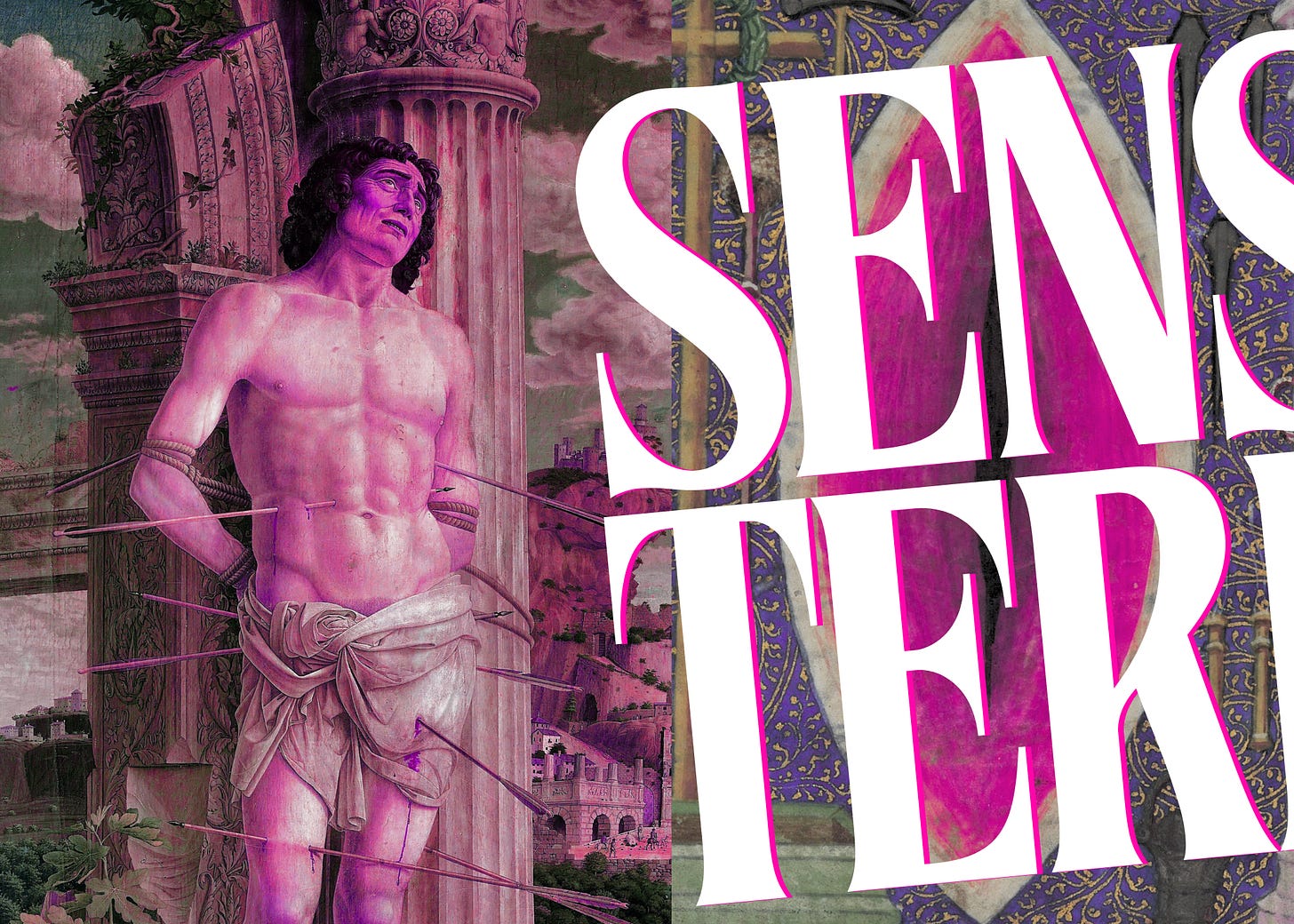

Welcome to the weekly dispatch, SENSUAL TERRORS: musings on creativity, movie culture, and some strange bits of life.

Content warning: While this does not include any excessively bloody images, this installment includes historical and contemporary imagery of wounds, including a religious painting, a prayer book illustration, and screencaps of SFX from the late 1980s.

The best part of my lore is that I am a lapsed Catholic. If you want to understand my pious neuroticism, aesthetic hedonism, and most importantly, my tortured relationship with sexuality, then you have to understand that I was Catholic for about 10 years.

That Catholic guilt and self-flagellation is real: Everyone is a liberal, bra-burning feminist until you have to go get your STI test and you randomly burst into tears because your intrusive thought is, “What if God gives you cervical cancer to punish you for having faggot-y premarital sex?

And somehow, despite all my programming, I was brave enough this year to go out on a limb and use the term “wound-fucking” in an essay.

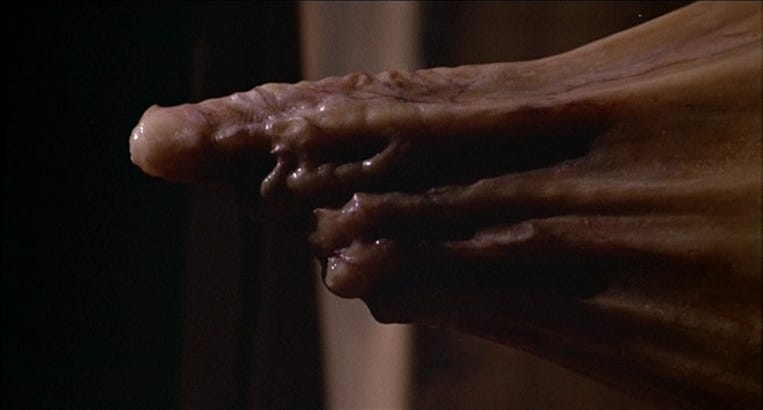

But I can’t think of a better word to describe that imagery from David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983). It was the second Cronenberg film I watched, following Crimes of the Future (2022), and I peeped Cronenberg’s game quickly: A little bit of innuendo, a lot of overtly slutty energy.

I clocked an undeniable BDSM undercurrent to the snuff videos that get broadcast on the fictional TV station at the center of the movie. And that detail alone adds an extra layer of taboo for me as an IRL journalist. I went to J-school right when Nightcrawler came out (2014) and captivated me,1 and we were told how to handle the old adage “If it bleeds, it leads” with tact.

Airing snuff, even on a “pirate” TV station, is unimaginable to me. So is the way protagonist Max Renn hooks up with his frenemy, Nicki Brand — a seduction highly screencapped and gif’d by freaky cinephiles from Tumblr to Instagram.

I count how many times I’ve seen the bit where Max emphasizes that the videotapes at his house feature torture and murder, to which, Nicki, played by the mesmerizing Debbie Harry, responds, “Sounds great.”

“Ain't exactly sex,” Max says.

“Says who?” Nicki quips.

Cronenberg, the master of perversion, layers sin on top of sin, and that’s how we get to the wound-fucking. First, there’s regular fucking, then you fall down a rabbit hole of sin.

Tech feels like flesh. Movies are sentient. Digital networks are leveraged for mind control. You can penetrate your skin and live to tell the tale of the agony over and over again.

That’s how a man ends up with a fuckable wound on his stomach.

After I watched Videodrome for the first time this year, I was thrilled to stumble across zombie grrrl zine, who has written at length about wounds as visual allegories for internal sex organs.

Zoe’s essay on the literary function of cannibalism thrilled me two-fold.

First, Zoe’s writing gave me the courage. I thought to myself, “Wow, there is room for critical thought like mine, that wants to go deep on the weird, wonderful, mystical, perverse and divine in art.”

Secondly, I thought to myself, “So I can write about horror beyond palatable final girls. I can write about the deeply uncomfortable films that showcase, romanticize and even eroticize gore.”

And as a lapsed Catholic, my curiosity was piqued by the Holy Side Wound of Christ, as mentioned in her Zoe’s cannibalism essay.

“The wound, in taking on a distinctly vaginal look, becomes invitational. We ascribe it the feminine quality of the suggestion of being able to be penetrated,” Zoe writes. “It is an invitation to eroticize and queer the body of Christ, specifically the wounds inflicted on him during the passion.”

As someone who spent a lot of time thinking about saints and holy death as a teenager, this wound brought to mind another Catholic work which has lived rent-free in my imagination since high school: The death of St. Sebastian.

It is an event that has been depicted countless times — from the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian by Andrea Mantegna (c.1480) to Esquire’s Esquire’s depiction of Muhammad Ali.

More than the ropes evoking shibari-esque imagery, it’s the entry points of the arrows that stand out to me. My first thought seeing Sebastian’s arrows is that they evoke a ticklishness in me.

While being tickled is not one of my kinks, I did sit for a tickling session at the local kink club’s open house once. This was the same night I laid in a coffin, by the way.

Anyway, being tied down and tickled by an effusive older White couple was not on my bingo card, but it was fun in very playful, carefree way.

I had an ongoing conversation with friends earlier this year about whether kink could be non-sexual. I don’t know if I have a definitive answer to that question, even as a former sex educator. But there was definitely a strong energy exchange — an arguably religious euphoria — to being caressed by the tender arrows of the couple’s roving hands.

Weighing the death of St. Sebastian, remembering how it feels to be pinned and penetrated, and recalling Catholicism’s emphasis on the Seven Sacraments of “outward signs of inward grace,” it’s not hard for me to wrap my head around the pulsing sexuality inherent to Max Renn’s gaping stomach.

This train of thought became even more delicious and layered when I realized that some people read Max Renn as a Christ-like figure, and there has been ongoing debate about Videodrome against or within a Christian context.

I go back to Zoe from zombie grrrl zine2, and the way she digs in further on Christ and his wounds:

Christianity presents us with instances wherein the potential for something to “get in” is something that is welcomed: it introduces a sanctity/holiness in consumption, penetration, and suffering.

Christianity sanctifies the transgression of borders, the welcoming in of something: inhabiting that liminal space becomes something positive.

With Christ, the consumption of his body and blood through communion is viewed as a way of allowing him to live on through another body.

I find Videodrome so interesting because of the ongoing transformation of Max’s body, a site of evolution and destruction involving foreign objects.

I can’t help but think of Zoe’s observation of Christ’s physical form, as depicted in religious art: “The body’s surface/border is crossed, and by inhabiting another body (through being consumed), the object exists through the subject.”

Who knows if Cronenberg looked to the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg or Catholicism as a whole for his inspiration.

But at the very least, centuries of religion have surely laid the foundation for our fascination with embodied gore — the kind that’s all up and through Videodrome.

For more on the queering of religious bodies through wound imagery, I recommend “Mysticism and queer readings of Christ’s Side Wound in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg” by Dr. Maeve K. Doyle.

Quiet as it’s kept, Nightcrawler had my whole family in a chokehold when we saw it.

I’m biased, but I can’t recommend Zoe’s musings enough.

This is my Roman Empire. Thank you from a person who spent their teenage years so bewildered by why my sexual awakening involved Jesus and the crucifixion, lol.

Terrific essay.